Chapter 2 The One-to-Many Relationship

Cow of many—well milked and badly fed.

Spanish proverb

Learning Objectives

Students completing this chapter will be able to

- write queries for a database with a one-to-many relationship.

2.1 Relationships

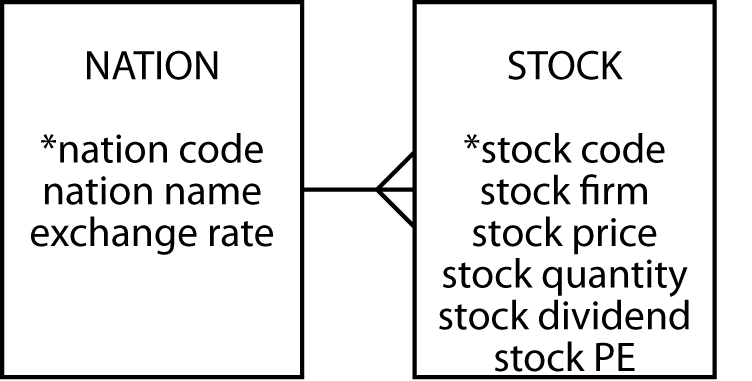

Entities are not isolated; they are related to other entities. When we move beyond the single entity, we need to identify the relationships between entities to accurately represent the real world. Consider the case where a person’s stocks are listed in different countries. We now need to introduce an entity called NATION. We now have two entities, STOCK and NATION. Consider the relationship between them. A NATION can have many listed stocks. A stock, in this case, is listed in only one nation. There is a 1:m (one-to-many) relationship between NATION and STOCK.

A 1:m relationship between two entities is depicted by a line connecting the two with a crow’s foot at the many end of the relationship. The following figure shows the 1:m relationship between NATION and STOCK. This can be read as: “a nation can have many stocks, but a stock belongs to only one nation.” The entity NATION is identified by nation code and has attributes nation name and exchange rate.

A 1:m relationship between NATION and STOCK

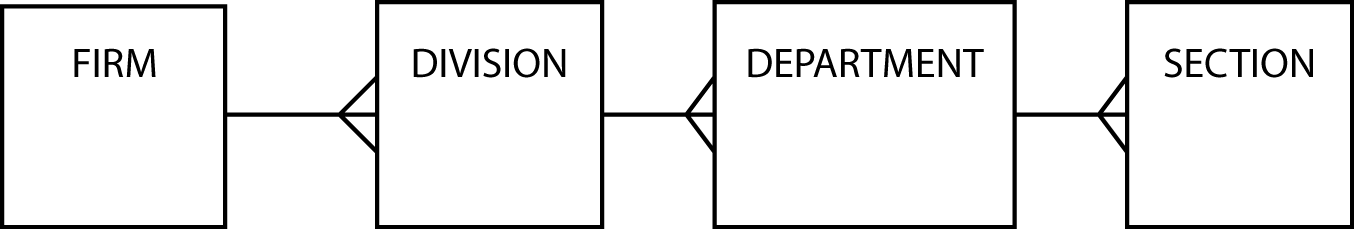

The 1:m relationship occurs frequently in business situations. Sometimes it occurs in a tree or hierarchical fashion. Consider a very hierarchical firm. It has many divisions, but a division belongs to only one firm. A division has many departments, but a department belongs to only one division. A department has many sections, but a section belongs to only one department.

A series of 1:m relationships

2.1.1 Why did we create an additional entity?

Another approach to adding data about listing nation and exchange rate is to add two attributes to STOCK: nation name and exchange rate. At first glance, this seems a very workable solution; however, this will introduce considerable redundancy, as the following table illustrates.

The table stock with additional columns

| *stkcode | stkfirm | stkprice | stkqty | stkdiv | stkpe | natname | exchrate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC | Freedonia Copper | 27.5 | 10529 | 1.84 | 16 | United Kingdom | 1 |

| PT | Patagonian Tea | 55.25 | 12635 | 2.5 | 10 | United Kingdom | 1 |

| AR | Abyssinian Ruby | 31.82 | 22010 | 1.32 | 13 | United Kingdom | 1 |

| SLG | Sri Lankan Gold | 50.37 | 32868 | 2.68 | 16 | United Kingdom | 1 |

| ILZ | Indian Lead & Zinc | 37.75 | 6390 | 3 | 12 | United Kingdom | 1 |

| BE | Burmese Elephant | 0.07 | 154713 | 0.01 | 3 | United Kingdom | 1 |

| BS | Bolivian Sheep | 12.75 | 231678 | 1.78 | 11 | United Kingdom | 1 |

| NG | Nigerian Geese | 35 | 12323 | 1.68 | 10 | United Kingdom | 1 |

| CS | Canadian Sugar | 52.78 | 4716 | 2.5 | 15 | United Kingdom | 1 |

| ROF | Royal Ostrich Farms | 33.75 | 1234923 | 3 | 6 | United Kingdom | 1 |

| MG | Minnesota Gold | 53.87 | 816122 | 1 | 25 | USA | 0.67 |

| GP | Georgia Peach | 2.35 | 387333 | 0.2 | 5 | USA | 0.67 |

| NE | Narembeen Emu | 12.34 | 45619 | 1 | 8 | Australia | 0.46 |

| QD | Queensland Diamond | 6.73 | 89251 | 0.5 | 7 | Australia | 0.46 |

| IR | Indooroopilly Ruby | 15.92 | 56147 | 0.5 | 20 | Australia | 0.46 |

| BD | Bombay Duck | 25.55 | 167382 | 1 | 12 | India | 0.0228 |

The exact same nation name and exchange rate pair occurs 10 times for stocks listed in the United Kingdom. This redundancy presents problems when we want to insert, delete, or update data. These problems, generally known as update anomalies, occur with these three basic operations.

2.1.1.1 Insert anomalies

We cannot insert a fact about a nation’s exchange rate unless we first buy a stock that is listed in that nation. Consider the case where we want to keep a record of France’s exchange rate and we have no French stocks. We cannot skirt this problem by putting in a null entry for stock details because stkcode, the primary key, would be null, and this is not allowed. If we have a separate table for facts about a nation, then we can easily add new nations without having to buy stocks. This is particularly useful when other parts of the organization, say International Trading, also need access to exchange rates for many nations.

2.1.1.2 Delete anomalies

If we delete data about a particular stock, we might also lose a fact about exchange rates. For example, if we delete details of Bombay Duck, we also erase the Indian exchange rate.

2.1.1.3 Update anomalies

Exchange rates are volatile. Most companies need to update them every day. What happens when the Australian exchange rate changes? Every row in stock with nation = ‘Australia’ will have to be updated. In a large portfolio, many rows will be changed. There is also the danger of someone forgetting to update all the instances of the nation and exchange rate pair. As a result, there could be two exchange rates for the one nation. If exchange rate is stored in a nation table, however, only one change is necessary, there is no redundancy, and there is no danger of inconsistent exchange rates.

The 1:m relationship is mapped by adding a column to the entity at the many end of the relationship. The additional column contains the identifier of the one end of the relationship.

Consider the relationship between the entities STOCK and NATION. The database has two tables: stock and nation. The table stock has an additional column, natcode, which contains the primary key of nation. If natcode is not stored in stock, then there is no way of knowing the identity of the nation where the stock is listed.

A relational database with tables nation and stock

| nation | ||

|---|---|---|

| *natcode | natname | exchrate |

| AUS | Australia | 0.46 |

| IND | India | 0.0228 |

| UK | United Kingdom | 1 |

| USA | United States | 0.67 |

| stock | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *stkcode | stkfirm | stkprice | stkqty | stkdiv | stkpe | natcode |

| FC | Freedonia Copper | 27.5 | 10,529 | 1.84 | 16 | UK |

| PT | Patagonian Tea | 55.25 | 12,635 | 2.5 | 10 | UK |

| AR | Abyssinian Ruby | 31.82 | 22,010 | 1.32 | 13 | UK |

| SLG | Sri Lankan Gold | 50.37 | 32,868 | 2.68 | 16 | UK |

| ILZ | Indian Lead & Zinc | 37.75 | 6,390 | 3 | 12 | UK |

| BE | Burmese Elephant | 0.07 | 154,713 | 0.01 | 3 | UK |

| BS | Bolivian Sheep | 12.75 | 231,678 | 1.78 | 11 | UK |

| NG | Nigerian Geese | 35 | 12,323 | 1.68 | 10 | UK |

| CS | Canadian Sugar | 52.78 | 4,716 | 2.5 | 15 | UK |

| ROF | Royal Ostrich Farms | 33.75 | 1,234,923 | 3 | 6 | UK |

| MG | Minnesota Gold | 53.87 | 816,122 | 1 | 25 | USA |

| GP | Georgia Peach | 2.35 | 387,333 | 0.2 | 5 | USA |

| NE | Narembeen Emu | 12.34 | 45,619 | 1 | 8 | AUS |

| QD | Queensland Diamond | 6.73 | 89,251 | 0.5 | 7 | AUS |

| IR | Indooroopilly Ruby | 15.92 | 56,147 | 0.5 | 20 | AUS |

| BD | Bombay Duck | 25.55 | 167,382 | 1 | 12 | IND |

Notice that natcode appears in both the stock and nation tables. In nation, natcode is the primary key; it is unique for each instance of nation. In table stock, natcode is a foreign key because it is the primary key of nation, the one end of the 1:m relationship. The column natcode is a foreign key in stock because it is a primary key in nation. A matched primary key–foreign key pair is the method for recording the 1:m relationship between the two tables. This method of representing a relationship is illustrated using shading and arrows for the two USA stocks. In the stock table, natcode is italicized to indicate that it is a foreign key. This method, like asterisking a primary key, is a useful reminder.

Although the same name has been used for the primary key and the foreign key in this example, it is not mandatory. The two columns can have different names, and in some cases you are forced to use different names. When possible, we find it convenient to use identical column names to help us remember that the tables are related. To distinguish between columns with identical names, they must by qualified by prefixing the table name. In this case, use nation.natcode and stock.natcode. Thus, nation.natcode refers to the natcode column in the table nation.

Although a nation can have many stocks, it is not mandatory to have any. That is, in data modeling terminology, many can be zero, one, or more, but it is mandatory to have a value for natcode in nation for every value of natcode in stock. This requirement, known as the referential integrity constraint, helps maintain the accuracy of a database. Its application means that every foreign key in a table has an identical primary key in that same table or another table. In this example, it means that for every value of natcode in stock, there is a corresponding entry in nation. As a result, a primary key row must be created before its corresponding foreign key row. In other words, details for a nation must be added before any data about its listed stocks are entered.

Every foreign key must have a matching primary key (referential integrity rule), and every primary key must be non-null (entity integrity rule). A foreign key cannot be null when a relationship is mandatory, as in the case where a stock must belong to a nation. If a relationship is optional (a person can have a boss), then a foreign key can be null (i.e., a person is the head of the organization, and thus has no boss). The ideas of mandatory and optional will be discussed later in this book.

Why is the foreign key in the table at the “many” end of the relationship? Because each instance of stock is associated with exactly one instance of nation. The rule is that a stock must be listed in one, and only one, nation. Thus, the foreign key field is single-valued when it is at the “many” end of a relationship. The foreign key is not at the “one” end of the relationship because each instance of nation can be associated with more than one instance of stock, and this implies a multivalued foreign key. The relational model does not support multivalued fields.

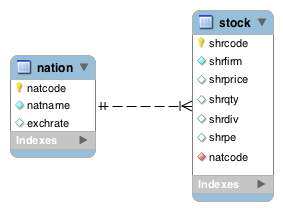

2.1.2 MySQL Workbench

In Workbench, a 1:m relationship is represented in a similar manner to the method you have just learned. Also, note that the foreign key is shown in the entity at the many end with a red diamond. We omit the foreign key when data modeling because it can be inferred.

Specifying a 1:m relationship in MySQL Workbench

2.2 Querying a two-table database

A two-table database offers the opportunity to learn more SQL and another relational algebra operation: join.

2.2.1 Join

Join creates a new table from two existing tables by matching on a column common to both tables. Usually, the common column is a primary key–foreign key pair: The primary key of one table is matched with the foreign key of another table. Join is frequently used to get the data for a query into a single row. Consider the tables nation and stock. If we want to calculate the value—in British pounds—of a stock, we multiply stock price by stock quantity and then exchange rate. To find the appropriate exchange rate for a stock, get its natcode from stock and then find the exchange rate in the matching row in nation, the one with the same value for natcode. For example, to calculate the value of Georgia Peach, which has natcode = ‘US’, find the row in nation that also has natcode = ‘US’. In this case, the stock’s value is 2.35 * 387333 / 0.67 = £609,855.81.

Calculation of stock value is very easy once a join is used to get the three values in one row. The SQL command for joining the two tables is:

SELECT * FROM stock JOIN nation

ON stock.natcode = nation.natcode;| stkcode | stkfirm | stkprice | stkqty | stkdiv | stkpe | natcode | natcode | natname | exchrate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR | Indooroopilly Ruby | 15.92 | 56147 | 0.50 | 20 | AUS | AUS | Australia | 0.4600 |

| NE | Narembeen Emu | 12.34 | 45619 | 1.00 | 8 | AUS | AUS | Australia | 0.4600 |

| QD | Queensland Diamond | 6.73 | 89251 | 0.50 | 7 | AUS | AUS | Australia | 0.4600 |

| BD | Bombay Duck | 25.55 | 167382 | 1.00 | 12 | IND | IND | India | 0.0228 |

| AR | Abyssinian Ruby | 31.82 | 22010 | 1.32 | 13 | UK | UK | United Kingdom | 1.0000 |

| BE | Burmese Elephant | 0.07 | 154713 | 0.01 | 3 | UK | UK | United Kingdom | 1.0000 |

| BS | Bolivian Sheep | 12.75 | 231678 | 1.78 | 11 | UK | UK | United Kingdom | 1.0000 |

| CS | Canadian Sugar | 52.78 | 4716 | 2.50 | 15 | UK | UK | United Kingdom | 1.0000 |

| FC | Freedonia Copper | 27.50 | 10529 | 1.84 | 16 | UK | UK | United Kingdom | 1.0000 |

| ILZ | Indian Lead & Zinc | 37.75 | 6390 | 3.00 | 12 | UK | UK | United Kingdom | 1.0000 |

The join of stock and nation

The columns stkprice and stkdiv record values in the country’s currency. Thus, the price of Bombay Duck is 25.55 Indian rupees. To find the value in U.K. pounds (GPB), multiply the price by 0.0228, because one rupee is worth 0.0228 GPB. The value of one share of Bombay Duck in U.S. dollars (USD) is 25.55 * 0.0228 / 0.67 because one USD is worth 0.67 GBP.

There are several things to notice about the SQL command and the result:

To avoid confusion because

natcodeis a column name in both stock and nation, it needs to be qualified. Ifnatcodeis not qualified, the system will reject the query because it cannot distinguish between the two columns titlednatcode.The new table has the

natcodecolumn replicated. Both are callednatcode. The naming convention for the replicated column varies with the RDBMS. The columns, for example, should be labeledstock.natcodeandnation.natcode.The SQL command specifies the names of the tables to be joined, the columns to be used for matching, and the condition for the match (equality in this case).

The number of columns in the new table is the sum of the columns in the two tables.

The stock value calculation is now easily specified in an SQL command because all the data are in one row.

Remember that during data modeling we created two entities, STOCK and NATION, and defined the relationship between them. We showed that if the data were stored in one table, there could be updating problems. Now, with a join, we have combined these data. So why separate the data only to put them back together later? There are two reasons. First, we want to avoid update anomalies. Second, as you will discover, we do not join the same tables every time.

A join can be combined with other SQL commands.

Report the value of each stockholding in UK pounds. Sort the report by nation and firm.

SELECT natname, stkfirm, stkprice, stkqty, exchrate,

stkprice*stkqty*exchrate as stkvalue

FROM stock JOIN nation

ON stock.natcode = nation.natcode

ORDER BY natname, stkfirm;| natname | stkfirm | stkprice | stkqty | exchrate | stkvalue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Indooroopilly Ruby | 15.92 | 56147 | 0.4600 | 411175.71 |

| Australia | Narembeen Emu | 12.34 | 45619 | 0.4600 | 258951.69 |

| Australia | Queensland Diamond | 6.73 | 89251 | 0.4600 | 276303.25 |

| India | Bombay Duck | 25.55 | 167382 | 0.0228 | 97506.71 |

| United Kingdom | Abyssinian Ruby | 31.82 | 22010 | 1.0000 | 700358.20 |

| United Kingdom | Bolivian Sheep | 12.75 | 231678 | 1.0000 | 2953894.50 |

| United Kingdom | Burmese Elephant | 0.07 | 154713 | 1.0000 | 10829.91 |

| United Kingdom | Canadian Sugar | 52.78 | 4716 | 1.0000 | 248910.48 |

| United Kingdom | Freedonia Copper | 27.50 | 10529 | 1.0000 | 289547.50 |

| United Kingdom | Indian Lead & Zinc | 37.75 | 6390 | 1.0000 | 241222.50 |

2.2.2 GROUP BY—reporting by groups

The GROUP BY clause is an elementary form of control break reporting. It permits grouping of rows that have the same value for a specified column or columns, and it produces one row for each different value of the grouping column(s).

Report by nation the total value of stockholdings.

SELECT natname, sum(stkprice*stkqty*exchrate) as stkvalue

FROM stock JOIN nation ON stock.natcode = nation.natcode

GROUP BY natname;| natname | stkvalue |

|---|---|

| Australia | 946430.65 |

| India | 97506.71 |

| United Kingdom | 48908364.25 |

| United States | 30066065.54 |

SQL’s built-in functions (COUNT, SUM, AVERAGE, MIN, and MAX) can be used with the GROUP BY clause. They are applied to a group of rows having the same value for a specified column. You can specify more than one function in a SELECT statement. For example, we can compute total value and number of different stocks and group by nation using:

Report the number of stocks and their total value by nation.

SELECT natname, COUNT(*), SUM(stkprice*stkqty*exchrate) AS stkvalue

FROM stock JOIN nation ON stock.natcode = nation.natcode

GROUP BY natname;| natname | COUNT(*) | stkvalue |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | 3 | 946430.65 |

| India | 1 | 97506.71 |

| United Kingdom | 10 | 48908364.25 |

| United States | 2 | 30066065.54 |

You can group by more than one column name; however, all column names appearing in the SELECT clause must be associated with a built-in function or be in a GROUP BY clause.

List stocks by nation, and for each nation show the number of stocks for each PE ratio and the total value of those stock holdings in UK pounds.

SELECT natname,stkpe,COUNT(*),

SUM(stkprice*stkqty*exchrate) AS stkvalue

FROM stock JOIN nation ON stock.natcode = nation.natcode

GROUP BY natname, stkpe;| natname | stkpe | COUNT(*) | stkvalue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 20 | 1 | 411175.71 |

| Australia | 8 | 1 | 258951.69 |

| Australia | 7 | 1 | 276303.25 |

| India | 12 | 1 | 97506.71 |

| United Kingdom | 13 | 1 | 700358.20 |

| United Kingdom | 3 | 1 | 10829.91 |

| United Kingdom | 11 | 1 | 2953894.50 |

| United Kingdom | 15 | 1 | 248910.48 |

| United Kingdom | 16 | 2 | 1945108.66 |

| United Kingdom | 12 | 1 | 241222.50 |

| United Kingdom | 10 | 2 | 1129388.75 |

| United Kingdom | 6 | 1 | 41678651.25 |

| United States | 5 | 1 | 609855.81 |

| United States | 25 | 1 | 29456209.73 |

In this example, stocks are grouped by both natname and stkpe. In most cases, there is only one stock for each pair of natname and stkpe; however, there are two situations (U.K. stocks with PEs of 10 and 16) where details of multiple stocks are grouped into one report line. Examining the values in the COUNT column helps you to identify these stocks.

2.2.3 HAVING—the WHERE clause of groups

The HAVING clause in a GROUP BY is like the WHERE clause in a SELECT. It restricts the number of groups reported, whereas WHERE restricts the number of rows reported. Used with built-in functions, HAVING is always preceded by GROUP BY and is always followed by a function (SUM, AVG, MAX, MIN, or COUNT).

Report the total value of stocks for nations with two or more listed stocks.

SELECT natname, SUM(stkprice*stkqty*exchrate) AS stkvalue

FROM stock JOIN nation ON stock.natcode = nation.natcode

GROUP BY natname

HAVING COUNT(*) >= 2;| natname | stkvalue |

|---|---|

| Australia | 946430.6 |

| United Kingdom | 48908364.2 |

| United States | 30066065.5 |

❓ Skill builder

Report by nation the total value of dividends.

2.3 Regular expression—pattern matching

Regular expression was introduced in the previous chapter, and we will now continue to learn some more of its features.

2.3.1 Search for a string not containing specified characters

The ^ (carat) is the symbol for NOT. It is used when we want to find a string not containing a character in one or more specified strings. For example, [^a-f] means any character not in the set containing a, b, c, d, e, or f.

List the names of nations with non-alphabetic characters in their names

SELECT natname FROM nation WHERE natname REGEXP '[^a-z|A-Z]'| natname |

|---|

| United Kingdom |

| United States |

Notice that the nations reported have a space in their name, which is a character not in the range a-z and not in A-Z.

2.3.2 Search for string containing a repeated pattern or repetition

A pair of curly brackets is used to denote the repetition factor for a pattern. For example, {n} means repeat a specified pattern n times.

List the names of firms with a double ‘e’.

SELECT stkfirm FROM stock WHERE stkfirm REGEXP '[e]{2}';| stkfirm |

|---|

| Bolivian Sheep |

| Freedonia Copper |

| Narembeen Emu |

| Nigerian Geese |

| Queensland Diamond |

2.3.3 Search combining alternation and repetition

Regular expressions becomes very powerful when you combine several of the basic capabilities into a single search expression.

List the names of firms with a double ‘s’ or a double ‘n’.

SELECT stkfirm FROM stock WHERE stkfirm REGEXP '[s]{2}|[n]{2}';| stkfirm |

|---|

| Abyssinian Ruby |

| Minnesota Gold |

2.3.4 Search for multiple versions of a string

If you are interested in find a string containing several specified string, you can use the square brackets to indicate the sought strings. For example, [ea] means any character from the set containing e and a.

List the names of firms with names that include ‘inia’ or ‘onia’.

SELECT stkfirm FROM stock WHERE stkfirm REGEXP '[io]nia';| stkfirm |

|---|

| Abyssinian Ruby |

| Freedonia Copper |

| Patagonian Tea |

2.3.5 Search for a string in a particular position

Sometimes you might be interested in identifying a string with a character in a particular position.

Find firms with ‘t’ as the third letter of their name.

SELECT stkfirm FROM stock WHERE stkfirm REGEXP '^(.){2}t';| stkfirm |

|---|

| Patagonian Tea |

The regular expression has three elements:

^ indicates start searching at the beginning of the string;

(.){2} specifies that anything is acceptable for the next two characters;

t indicates what the next character, the third, must be.

2.3.6 Search for a string not containing any specified characters

There might be a need to find rows not containing specified characters anywhere in a givev coumn. You need to check every character in the string to ensure there are matches.

List the names of nations without s or S anywhere in their names

SELECT * FROM nation WHERE natname REGEXP '^[^s|S]*$'| natcode | natname | exchrate |

|---|---|---|

| IND | India | 0.0228 |

| UK | United Kingdom | 1.0000 |

- ^ start searching at the beginning of the string;

- $ end searching at the end of the string;

- * any character in a string;

- ^s|S no lower or upper case s.

You have seen a few of the features of a very powerful tool. To learn more about regular expressions, see regexlib.com, which contains a library of regular expressions and a feature for finding expressions to solve specific problems. Check out the regular expression for checking whether a character string is a valid email address.

Summary

Entities are related to other entities by relationships. The 1:m (one-to-many) relationship occurs frequently in data models. An additional entity is required to represent a 1:m relationship to avoid update anomalies. In a relational database, a 1:m relationship is represented by an additional column, the foreign key, in the table at the many end of the relationship. The referential integrity constraint insists that a foreign key must always exist as a primary key in a table. A foreign key constraint is specified in a CREATE statement.

Join creates a new table from two existing tables by matching on a column common to both tables. Often the common column is a primary key–foreign key combination. The GROUP BY clause is used to create an elementary control break report. The HAVING clause of GROUP BY is like the WHERE clause of SELECT. A subquery, which has a SELECT statement within another SELECT statement, causes two SELECT statements to be executed—one for the inner query and one for the outer query.

Key terms and concepts

| JOIN | |

| Control break reporting | One-to-many (1:m) relationship |

| Referential integrity | |

| Delete anomalies | Relationship |

| Foreign key | Update anomalies |

| GROUP BY | HAVING |

| Insert anomalies |

Exercises

Report all values in British pounds:

Report the value of stocks listed in Australia.

Report the dividend payment of all stocks.

Report the total dividend payment by nation.

Create a view containing nation, firm, price, quantity, exchange rate, value, and yield.

Report the average yield by nation.

Report the minimum and maximum yield for each nation.

Report the nations where the average yield of stocks exceeds the average yield of all stocks.

How would you change the queries in exercise 4-2 if you were required to report the values in American dollars, Australian dollars, or Indian rupees?

- Find stocks where the third or fourth letter in their name is an ‘m’.