Chapter 1 The Single Entity

I want to be alone.

Attributed to Greta Garbo

Learning Objectives

Students completing this chapter will be able to

- write queries for a single-table database.

1.1 The relational model

The relational model introduced by Codd in 1970 is the most popular technology for managing large collections of data. In this chapter, the major concepts of the relational model are introduced. Extensive coverage of the relational model is left until Chapter 8, by which time you will have sufficient practical experience to appreciate fully its usefulness, value, and elegance.

A relation, similar to the mathematical concept of a set, is a two-dimensional table arranged in rows and columns. This is a very familiar idea. You have been using tables for many years. A relational database is a collection of relations, where relation is a mathematical term for a table. One row of a table stores details of one observation, instance, or case of an item about which facts are retained—for example, one row for details of a particular student. All the rows in a table store data about the same type of item. Thus, a database might have one table for student data and another table for class data. Similarly, each column in the table contains the same type of data. For example, the first column might record a student’s identification number. A key database design question is to decide what to store in each table. What should the rows and columns contain?

In a relational database, each row must be uniquely identified. There must be a primary key, such as student identifier, so that a particular row can be designated. The use of unique identifiers is very common. Telephone numbers and e-mail addresses are examples of unique identifiers. Selection of the primary key, or unique identifier, is another key issue of database design.

💠 Global legal entity identifier (LEI)

There is no global standard for identifying legal entities across markets and jurisdictions. The need for such a standard was amplified by Lehman Brothers collapse in 2008. Lehman had 209 registered subsidiaries, legal entities, in 21 countries, and it was party to more than 900,000 derivatives contracts upon its collapse. Key stakeholders, such as financial regulators and Lehman’s creditors, were unable to assess their exposure. Furthermore, others were unable to assess the possible ripple on them of the effects of the collapse because of the transitive nature of many investments (i.e., A owes B, B owes C, and C owes D).

The adoption of a global legal entity identifier (LEI), should improve financial system regulation and corporate risk management. Regulators will find it easier to monitor and analyze threats to financial stability and risk managers will be more able evaluate their companies’ risks.

The tables in a relational database are connected or related by means of the data in the tables. You will learn, in the next chapter, that this connection is through a pair of values—a primary key and a foreign key. Consider a table of airlines serving a city. When examining this table, you may not recognize the code of an airline, so you then go to another table to find the name of the airline. For example, if you inspect the next table, you find that AM is an international airline serving Atlanta.

International airlines serving Atlanta

| Airline |

|---|

| AM |

| JL |

| KX |

| LM |

| MA |

| OS |

| RG |

| SN |

| SR |

| LH |

| LY |

If you don’t know which airline has the abbreviation AM, then you need to look at the table of airline codes to discover that AeroMexico, with code AM, serves Atlanta. The two tables are related by airline code. Later, you will discover which is the primary key and which is the foreign key.

A partial list of airline codes

| Code | Airline |

|---|---|

| AA | American Airlines |

| AC | Air Canada |

| AD | Lone Star Airlines |

| AE | Mandarin Airlines |

| AF | Air France |

| AG | Interprovincial Airlines |

| AI | Air India |

| AM | AeroMexico |

| AQ | Aloha Airlines |

When designing the relational model, Codd provided commands for processing multiple records at a time. His intention was to increase the productivity of programmers by moving beyond the record-at-a-time processing that is found in most programming languages. Consequently, the relational model supports set processing (multiple records-at-a-time), which is most frequently implemented as Structured Query Language (SQL).1

The relational model separates the logical design of a database from its physical storage. This notion of data independence simplifies data modeling and database programming. In this section, we focus on logical database design, and now that you have had a brief introduction to the relational model, you are ready to learn data modeling.

1.2 Getting started

As with most construction projects, building a relational database must be preceded by a design phase. Data modeling, our design technique, is a method for creating a plan or blueprint of a database. The data model must accurately mirror real-world relationships if it is to support processing business transactions and managerial decision making.

Rather than getting bogged down with a theory first, application later approach to database design and use, we will start with application. We will get back to theory when you have some experience in data modeling and database querying. After all, you did not learn to talk by first studying sentence formation; you just started by learning and using simple words. We start with the simplest data model, a single entity, and the simplest database, a single table, as follows.

| Share code | Share name | Share price | Share quantity | Share dividend | PE ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC | Freedonia Copper | 27.5 | 10,529 | 1.84 | 16 |

| PT | Patagonian Tea | 55.25 | 12,635 | 2.50 | 10 |

| AR | Abyssinian Ruby | 31.82 | 22,010 | 1.32 | 13 |

| SLG | Sri Lankan Gold | 50.37 | 32,868 | 2.68 | 16 |

| ILZ | Indian Lead & Zinc | 37.75 | 6,390 | 3.00 | 12 |

| BE | Burmese Elephant | 0.07 | 154,713 | 0.01 | 3 |

| BS | Bolivian Sheep | 12.75 | 231,678 | 1.78 | 11 |

| NG | Nigerian Geese | 35.00 | 12,323 | 1.68 | 10 |

| CS | Canadian Sugar | 52.78 | 4,716 | 2.50 | 15 |

| ROF | Royal Ostrich Farms | 33.75 | 1,234,923 | 3.00 | 6 |

1.3 Modeling a single-entity database

The simplest database contains information about one entity, which is some real-world thing. Some entities are physical—CUSTOMER, ORDER, and STUDENT; others are abstract or conceptual—WORK ASSIGNMENT, and AUTHORSHIP. We represent an entity by a rectangle: the following figure shows a representation of the entity SHARE. The name of the entity is shown in singular form in uppercase in the top part of the rectangle.

The entity SHARE

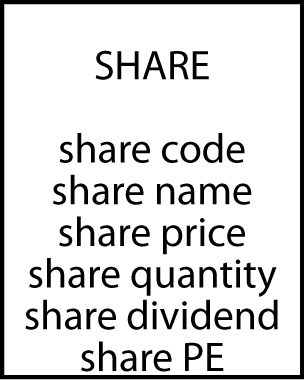

An entity has characteristics or attributes. An attribute is a discrete element of data; it is not usually broken down into smaller components. Attributes are describe the data we want to store. Some attributes of the entity SHARE are share code, share name, share price, share quantity (number owned), share dividend, and PE ratio (price-to-earnings ratio).2 Attributes are shown below the entity’s name. Notice that we refer to share price, rather than price, to avoid confusion if there should be another entity with an attribute called price. Attribute names must be carefully selected so that they are self-explanatory and unique. For example, share dividend is easily recognized as belonging to the entity SHARE.

The entity SHARE and its attributes

An instance is a particular occurrence of an entity (e.g., facts about Freedonia Copper). To avoid confusion, each instance of an entity needs to be uniquely identified. Consider the case of customer billing. In most cases, a request to bill Smith $100 cannot be accurately processed because a firm might have more than one Smith in its customer file. If a firm has carefully controlled procedures for ensuring that each customer has a unique means of identification, then a request to bill customer number 1789 $100 can be accurately processed. An attribute or collection of attributes that uniquely identifies an instance of an entity is called an identifier. The identifier for the entity SHARE is share code, a unique identifier assigned by the stock exchange to a firm issuing shares.

There may be several attributes, or combinations of attributes, that are feasible identifiers for an instance of an entity. Attributes that are identifiers are prefixed by an asterisk. The following figure shows an example of a representation of an entity, its attributes, and identifier.

The entity SHARE, its attributes, and identifier

Briefly, entities are things in the environment about which we wish to store information. Attributes describe an entity. An entity must have a unique identifier.

In this book, MySQL is the relational database for teaching SQL. Because SQL is a standard, it does not matter which implementation of the relational model you use as the SQL language is common across both the proprietary and open variants.[^singleentity-3]

SQL statements can be written in any mix of valid upper and lowercase characters. To make it easier for you to learn the syntax, this book adopts the following conventions:

SQL keywords are in uppercase.

Table and column names are in lowercase.

There are more elaborate layout styles, but we will bypass those because it is more important at this stage to learn SQL. You should lay out your SQL statements so that they are easily read by you and others.

The following table shows some of the data types supported by most relational databases. Other implementations of the relational model may support some of these data types and additional ones. It is a good idea to review the available data types in your RDBMS before defining your first table.

Some allowable data types

| Category | Data type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Numeric | SMALLINT | A 15-bit signed binary value |

| INTEGER | A 31-bit signed binary value | |

| FLOAT(p) | A scientific format number of p binary digits precision | |

| DECIMAL(p,q) | A packed decimal number of p digits total length; q decimal spaces to the right of the decimal point may be specified | |

| String | CHAR(n) | A fixed-length string of n characters |

| VARCHAR(n) | A variable-length string of up to n characters | |

| text | A variable-length string of up to 65,535 characters | |

| Date/time | DATE | Date in the form yyyymmdd |

| TIME | Time in the form hhmmss | |

| timesTAMP | A combination of date and time to the nearest microsecond | |

| time with time zone | Same as time, with the addition of an offset from universal time coordinated (UTC) of the specified time | |

| timestamp with time zone | Same as timestamp, with the addition of an offset from UTC of the specified time | |

| Logical | Boolean | A set of truth values: TRUE, FALSE, or UNKNOWN |

The CHAR and VARCHAR data types are similar but differ in the way character strings are stored and retrieved. Both can be up to 255 characters long. The length of a CHAR column is fixed to the declared length. When values are stored, they are right-padded with spaces to the specified length. When CHAR values are retrieved, trailing spaces are removed. VARCHAR columns store variable-length strings and use only as many characters as are needed to store the string. Values are not padded; instead, trailing spaces are removed. In this book, we use VARCHAR to define most character strings, unless they are short (less than five characters is a good rule-of-thumb).

The data for the share table will be used in subsequent examples. If you have ready access to a relational database, it is a good idea to now create a table and enter the data. Then you will be able to use these data to practice querying the table.

Data for share

| *Code | Name | Price | Quantity | Dividend | PE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC | Freedonia Copper | 27.5 | 10,529 | 1.84 | 16 |

| PT | Patagonian Tea | 55.25 | 12,635 | 2.50 | 10 |

| AR | Abyssinian Ruby | 31.82 | 22,010 | 1.32 | 13 |

| SLG | Sri Lankan Gold | 50.37 | 32,868 | 2.68 | 16 |

| ILZ | Indian Lead & Zinc | 37.75 | 6,390 | 3.00 | 12 |

| BE | Burmese Elephant | 0.07 | 154,713 | 0.01 | 3 |

| BS | Bolivian Sheep | 12.75 | 231,678 | 1.78 | 11 |

| NG | Nigerian Geese | 35.00 | 12,323 | 1.68 | 10 |

| CS | Canadian Sugar | 52.78 | 4,716 | 2.50 | 15 |

| ROF | Royal Ostrich Farms | 33.75 | 1,234,923 | 3.00 | 6 |

1.4 Querying a single-table database

The objective of developing a database is to make it easier to use the stored data to solve problems. Typically, a manager raises a question (e.g., How many shares have a PE ratio greater than 12?). A question or request for information, usually called a query, is then translated into a specific data manipulation or query language. The most widely used query language for relational databases is SQL. After the query has been executed, the resulting data are displayed. In the case of a relational database, the answer to a query is always a table.

There is also a query language called relational algebra, which describes a set of operations on tables. Sometimes it is useful to think of queries in terms of these operations. Where appropriate, we will introduce the corresponding relational algebra operation.

Generally we use a four-phase format for describing queries:

A brief explanation of the query’s purpose

The query in italics, prefixed by •, and some phrasing you might expect from a manager

The SQL version of the query

The results of the query.

1.4.1 Displaying an entire table

All the data in a table can be displayed using the SELECT statement. In SQL, the all part is indicated by an asterisk (*).

List all data in the share table.

SELECT * FROM share;| shrcode | shrfirm | shrprice | shrqty | shrdiv | shrpe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR | Abyssinian Ruby | 31.82 | 22010 | 1.32 | 13 |

| BE | Burmese Elephant | 0.07 | 154713 | 0.01 | 3 |

| BS | Bolivian Sheep | 12.75 | 231678 | 1.78 | 11 |

| CS | Canadian Sugar | 52.78 | 4716 | 2.50 | 15 |

| FC | Freedonia Copper | 27.50 | 10529 | 1.84 | 16 |

| ILZ | Indian Lead & Zinc | 37.75 | 6390 | 3.00 | 12 |

| NG | Nigerian Geese | 35.00 | 12323 | 1.68 | 10 |

| PT | Patagonian Tea | 55.25 | 12635 | 2.50 | 10 |

| ROF | Royal Ostrich Farms | 33.75 | 1234923 | 3.00 | 6 |

| SLG | Sri Lankan Gold | 50.37 | 32868 | 2.68 | 16 |

1.4.2 Project—choosing columns

The relational algebra operation project creates a new table from the columns of an existing table. Project takes a vertical slice through a table by selecting all the values in specified columns. The projection of share on columns shrfirm and shrpe produces a new table with 10 rows and 2 columns. The SQL syntax for the project operation simply lists the columns to be displayed.

Report a firm’s name and price-earnings ratio.

SELECT shrfirm, shrpe FROM share;| shrfirm | shrpe |

|---|---|

| Abyssinian Ruby | 13 |

| Burmese Elephant | 3 |

| Bolivian Sheep | 11 |

| Canadian Sugar | 15 |

| Freedonia Copper | 16 |

| Indian Lead & Zinc | 12 |

| Nigerian Geese | 10 |

| Patagonian Tea | 10 |

| Royal Ostrich Farms | 6 |

| Sri Lankan Gold | 16 |

1.4.3 Restrict—choosing rows

The relational algebra operation restrict creates a new table from the rows of an existing table. The operation restricts the new table to those rows that satisfy a specified condition. Restrict takes all columns of an existing table but only those rows that meet the specified condition. The restriction of share to those rows where the PE ratio is less than 12 will give a new table with five rows and six columns.

Restrict is implemented in SQL using the WHERE clause to specify the condition on which rows are restricted.

Get all firms with a price-earnings ratio less than 12.

SELECT * FROM share WHERE shrpe < 12;| shrcode | shrfirm | shrprice | shrqty | shrdiv | shrpe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BE | Burmese Elephant | 0.07 | 154713 | 0.01 | 3 |

| BS | Bolivian Sheep | 12.75 | 231678 | 1.78 | 11 |

| NG | Nigerian Geese | 35.00 | 12323 | 1.68 | 10 |

| PT | Patagonian Tea | 55.25 | 12635 | 2.50 | 10 |

| ROF | Royal Ostrich Farms | 33.75 | 1234923 | 3.00 | 6 |

In this example, we have a less than condition for the WHERE clause. All permissible comparison operators are listed below.

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

| = | Equal to |

| < | Less than |

| <= | Less than orequal to |

| > | Greater than |

| >= | Greater than or equal to |

| <> | Not equal to |

In addition to the comparison operators, the BETWEEN construct is available.

The expression a BETWEEN x AND y is equivalent to a >= x AND a <= y.

1.4.4 Combining project and restrict—choosing rows and columns

SQL permits project and restrict to be combined. A single SQL SELECT statement can specify which columns to project and which rows to restrict.

List the name, price, quantity, and dividend of each firm where the share holding is at least 100,000.

SELECT shrfirm, shrprice, shrqty, shrdiv FROM share

WHERE shrqty >= 100000;| shrfirm | shrprice | shrqty | shrdiv |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burmese Elephant | 0.07 | 154713 | 0.01 |

| Bolivian Sheep | 12.75 | 231678 | 1.78 |

| Royal Ostrich Farms | 33.75 | 1234923 | 3.00 |

1.4.5 More about WHERE

The WHERE clause can contain several conditions linked by AND or OR. A clause containing AND means all specified conditions must be true for a row to be selected. In the case of OR, at least one of the conditions must be true for a row to be selected.

Find all firms where the PE is 12 or higher and the share holding is less than 10,000.

SELECT * FROM share

WHERE shrpe >= 12 AND shrqty < 10000;| shrcode | shrfirm | shrprice | shrqty | shrdiv | shrpe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | Canadian Sugar | 52.78 | 4716 | 2.5 | 15 |

| ILZ | Indian Lead & Zinc | 37.75 | 6390 | 3.0 | 12 |

1.4.6 The power of the primary key

The purpose the primary key is to guarantee that any row in a table can be uniquely addressed. In this example, we use shrcode to return a single row because shrcode is unique for each instance of share. The sought code (AR) must be specified in quotes because shrcode was defined as a character string when the table was created.

Report firms whose code is AR.

SELECT * FROM share WHERE shrcode = 'AR';| shrcode | shrfirm | shrprice | shrqty | shrdiv | shrpe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR | Abyssinian Ruby | 31.82 | 22010 | 1.32 | 13 |

A query based on a non-primary-key column cannot guarantee that a single row is accessed, as the following illustrates.

Report firms with a dividend of 2.50.

SELECT * FROM share WHERE shrdiv = 2.5;| shrcode | shrfirm | shrprice | shrqty | shrdiv | shrpe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | Canadian Sugar | 52.78 | 4716 | 2.5 | 15 |

| PT | Patagonian Tea | 55.25 | 12635 | 2.5 | 10 |

1.4.7 The IN crowd

The keyword IN is used with a list to specify a set of values. IN is always paired with a column name. All rows for which a value in the specified column has a match in the list are selected. It is a simpler way of writing a series of OR statements.

Report data on firms with codes of FC, AR, or SLG.

SELECT * FROM share WHERE shrcode IN ('FC','AR','SLG');The foregoing query could have also been written as

SELECT * FROM share

WHERE shrcode = 'FC' or shrcode = 'AR' or shrcode = 'SLG';| shrcode | shrfirm | shrprice | shrqty | shrdiv | shrpe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR | Abyssinian Ruby | 31.82 | 22010 | 1.32 | 13 |

| FC | Freedonia Copper | 27.50 | 10529 | 1.84 | 16 |

| SLG | Sri Lankan Gold | 50.37 | 32868 | 2.68 | 16 |

1.4.8 The NOT IN crowd

A NOT IN list is used to report instances that do not match any of the values.

Report all firms other than those with the code CS or PT.

SELECT * FROM share WHERE shrcode NOT IN ('CS','PT');is equivalent to

SELECT * FROM share WHERE shrcode <> 'CS' AND shrcode <> 'PT';| shrcode | shrfirm | shrprice | shrqty | shrdiv | shrpe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR | Abyssinian Ruby | 31.82 | 22010 | 1.32 | 13 |

| BE | Burmese Elephant | 0.07 | 154713 | 0.01 | 3 |

| BS | Bolivian Sheep | 12.75 | 231678 | 1.78 | 11 |

| FC | Freedonia Copper | 27.50 | 10529 | 1.84 | 16 |

| ILZ | Indian Lead & Zinc | 37.75 | 6390 | 3.00 | 12 |

| NG | Nigerian Geese | 35.00 | 12323 | 1.68 | 10 |

| ROF | Royal Ostrich Farms | 33.75 | 1234923 | 3.00 | 6 |

| SLG | Sri Lankan Gold | 50.37 | 32868 | 2.68 | 16 |

❓ Skill Builder

List those shares where the value of the holding exceeds one million.

1.4.9 Ordering columns

The order of reporting columns is identical to their order in the SQL command. For instance, compare the output of the following queries.

SELECT shrcode, shrfirm FROM share WHERE shrpe = 10;| shrcode | shrfirm |

|---|---|

| NG | Nigerian Geese |

| PT | Patagonian Tea |

SELECT shrfirm, shrcode FROM share WHERE shrpe = 10;| shrfirm | shrcode |

|---|---|

| Nigerian Geese | NG |

| Patagonian Tea | PT |

1.4.10 Regular expression—pattern matching

Regular expression is a concise and powerful method for searching for a specified pattern in a nominated column. Regular expression processing is supported by languages such as Java, R, and PHP. In this chapter, we introduce a few typical regular expressions and will continue developing your knowledge of this feature in the next chapter.

1.4.10.1 Search for a string

List all firms containing ‘Ruby’ in their name.

SELECT shrfirm FROM share WHERE shrfirm REGEXP 'Ruby';| shrfirm |

|---|

| Abyssinian Ruby |

1.4.10.2 Search for alternative strings

In some situations you want to find columns that contain more than one string. In this case, we use the alternation symbol ‘|’ to indicate the alternatives being sought. For example, a|b finds ‘a’ or ‘b’.

List firms containing gold or zinc in their name, irrespective of case.

SELECT shrfirm FROM share WHERE shrfirm REGEXP 'gold|zinc|Gold|Zinc';| shrfirm |

|---|

| Indian Lead & Zinc |

| Sri Lankan Gold |

1.4.10.3 Search for a beginning string

If you are interested in finding a value in a column that starts with a particular character string, then use ^ to indicate this option.

List the firms whose name begins with Sri.

SELECT shrfirm FROM share WHERE shrfirm REGEXP '^Sri';| shrfirm |

|---|

| Sri Lankan Gold |

1.4.10.4 Search for an ending string

If you are interested in finding if a value in a column ends with a particular character string, then use $ to indicate this option.

List the firms whose name ends with Geese.

SELECT shrfirm FROM share WHERE shrfirm REGEXP 'Geese$';| shrfirm |

|---|

| Nigerian Geese |

❓ Skill builder

List the firms containing “ian” in their name.

1.4.11 Ordering rows

People can generally process an ordered (e.g., sorted alphabetically) report faster than an unordered one. In SQL, the ORDER BY clause specifies the row order in a report. The default ordering sequence is ascending (A before B, 1 before 2). Descending is specified by adding DESC after the column name.

List all firms where PE is at least 10, and order the report in descending PE. Where PE ratios are identical, list firms in alphabetical order.

SELECT * FROM share WHERE shrpe >= 10

ORDER BY shrpe DESC, shrfirm;| shrcode | shrfirm | shrprice | shrqty | shrdiv | shrpe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC | Freedonia Copper | 27.50 | 10529 | 1.84 | 16 |

| SLG | Sri Lankan Gold | 50.37 | 32868 | 2.68 | 16 |

| CS | Canadian Sugar | 52.78 | 4716 | 2.50 | 15 |

| AR | Abyssinian Ruby | 31.82 | 22010 | 1.32 | 13 |

| ILZ | Indian Lead & Zinc | 37.75 | 6390 | 3.00 | 12 |

| BS | Bolivian Sheep | 12.75 | 231678 | 1.78 | 11 |

| NG | Nigerian Geese | 35.00 | 12323 | 1.68 | 10 |

| PT | Patagonian Tea | 55.25 | 12635 | 2.50 | 10 |

1.4.12 Numeric versus character sorting

Numeric data in character fields (e.g., a product code) do not always sort the way you initially expect. The difference arises from the way data are stored:

Numeric fields are right justified and have leading zeros.

Character fields are left justified and have trailing spaces.

For example, the value 1066 stored as CHAR(4) would be stored as ‘1066’ and the value 45 would be stored as ‘45’. If the column containing these data is sorted in ascending order, then ‘1066’ precedes ‘45’ because the leftmost character ‘1’ is less than ‘4’. You can avoid this problem by always storing numeric values as numeric data types (e.g., integer or decimal) or preceding numeric values with zeros when they are stored as character data. Alternatively, start numbering at 1,000 so that all values are four digits, though the best solution is to store numeric data as numbers rather than characters.

1.4.13 Derived data

One of the important principles of database design is to avoid redundancy. One form of redundancy is including a column in a table when these data can be derived from other columns. For example, we do not need a column for yield because it can be calculated by dividing dividend by price and multiplying by 100 to obtain the yield as a percentage. This means that the query language does the calculation when the value is required.

Get firm name, price, quantity, and firm yield.

SELECT shrfirm, shrprice, shrqty, shrdiv/shrprice*100 AS yield FROM share;| shrfirm | shrprice | shrqty | yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abyssinian Ruby | 31.82 | 22010 | 4.148334 |

| Burmese Elephant | 0.07 | 154713 | 14.285714 |

| Bolivian Sheep | 12.75 | 231678 | 13.960784 |

| Canadian Sugar | 52.78 | 4716 | 4.736643 |

| Freedonia Copper | 27.50 | 10529 | 6.690909 |

| Indian Lead & Zinc | 37.75 | 6390 | 7.947020 |

| Nigerian Geese | 35.00 | 12323 | 4.800000 |

| Patagonian Tea | 55.25 | 12635 | 4.524887 |

| Royal Ostrich Farms | 33.75 | 1234923 | 8.888889 |

| Sri Lankan Gold | 50.37 | 32868 | 5.320627 |

You can give the results of the calculation a column name. In this case, a good choice is yield. Note the use of AS to indicate the name of the column in which the results of the calculation are displayed.

In the preceding query, the keyword AS is introduced to specify an alias, or temporary name. The statement specifies that the result of the calculation is to be reported under the column heading yield. You can rename any column or specify a name for the results of an expression using an alias.

1.4.14 Aggregate functions

SQL has built-in functions to enhance its retrieval power and handle many common aggregation queries, such as computing the total value of a column. Four of these functions (AVG, SUM, MIN, and MAX) work very similarly. COUNT is a little different.

1.4.14.1 COUNT

COUNT computes the number of rows in a table. Use COUNT(*) to count all rows irrespective of their content (i.e., null or not null), and use COUNT(columnname) to count rows without a null value for columname. Count can be used with a WHERE clause to specify a condition.

How many firms are there in the portfolio?

SELECT COUNT(shrcode) AS investments FROM share;| investments |

|---|

| 10 |

How many firms have a holding greater than 50,000?

SELECT COUNT(shrfirm) AS bigholdings FROM share WHERE shrqty > 50000;| bigholdings |

|---|

| 3 |

1.4.14.2 AVG—averaging

AVG computes the average of the values in a column of numeric data. Null values in the column are not included in the calculation.

Find the average dividend.

SELECT AVG(shrdiv) AS avgdiv FROM share;| avgdiv |

|---|

| 2.031 |

What is the average yield for the portfolio?

SELECT AVG(shrdiv/shrprice*100) AS avgyield FROM share;| avgyield |

|---|

| 7.530381 |

1.4.15 Subqueries

Sometimes we need the answer to another query before we can write the query of ultimate interest. For example, to list all shares with a PE ratio greater than the portfolio average, you first must find the average PE ratio for the portfolio. You could do the query in two stages:

SELECT AVG(shrpe) FROM share;and

SELECT shrfirm, shrpe FROM share WHERE shrpe > x;where x is the value returned from the first query.

Unfortunately, the two-stage method introduces the possibility of errors. You might forget the value returned by the first query or enter it incorrectly. It also takes longer to get the results of the query. We can solve these problems by using parentheses to indicate the first query is nested within the second one. As a result, the value returned by the inner or nested subquery, the one in parentheses, is used in the outer query. In the following example, the nested query returns 11.20, which is then automatically substituted in the outer query.

Report all firms with a PE ratio greater than the average for the portfolio.

SELECT shrfirm, shrpe FROM share

WHERE shrpe > (SELECT AVG(shrpe) FROM share);| shrfirm | shrpe |

|---|---|

| Abyssinian Ruby | 13 |

| Canadian Sugar | 15 |

| Freedonia Copper | 16 |

| Indian Lead & Zinc | 12 |

| Sri Lankan Gold | 16 |

⚠️ The preceding query is often mistakenly written as SELECT shrfirm, shrpe from share WHERE shrpe > avg(shrpe); You need to use a subquery to find the average, so the computed value can be used in the outer query

❓ Skill builder

Find the name of the firm for which the value of the holding is greatest.

1.4.15.1 DISTINCT—eliminating duplicate rows

The DISTINCT clause is used to eliminate duplicate rows. It can be used with column functions or before a column name. When used with a column function, it ignores duplicate values.

Report the different values of the PE ratio.

SELECT DISTINCT shrpe FROM share;| shrpe |

|---|

| 13 |

| 3 |

| 11 |

| 15 |

| 16 |

| 12 |

| 10 |

| 6 |

Find the number of different PE ratios.

SELECT COUNT(DISTINCT shrpe) as 'Different PEs' FROM share;| Different PEs |

|---|

| 8 |

When used before a column name, DISTINCT prevents the selection of duplicate rows. Notice a slightly different use of the keyword AS. In this case, because the alias includes a space, the entire alias is enclosed in straight quotes.

Quotes

There are three types of quotes that you can typically use with SQL. Double and single quotes are equivalent and can be used interchangeably. Note that single and double quotes must be straight rather than curly, and the back quote is to the left of the 1 key.

| Type of quote | Representation |

|---|---|

| Single | ’ |

| Double | “ |

| Back | ` |

The following SQL illustrates the use of three types of quotes to find a person with a last name of O’Hara and where the column names are person first and person last.

SELECT `person first` FROM person WHERE `person last` = "O'Hara";| person first |

|---|

| Sheila |

Summary

In SQL, queries are written using the SELECT statement. Project (choosing columns) and restrict (choosing rows) are common table operations. The WHERE clause is used to specify row selection criteria. WHERE can be combined with IN and NOT IN, which specify values for a single column. The rows of a report are sorted using the ORDER BY clause. Arithmetic expressions can appear in SQL statements, and SQL has built-in functions for common arithmetic operations. A subquery is a query within a query. Regular expressions are used to find string patterns within character strings. Duplicate rows are eliminated with the DISTINCT clause.

Key terms and concepts

| Alias | Instance |

| AS | MAX |

| Attribute | MIN |

| AVG | NOT IN |

| Column | ORDER BY |

| COUNT | Primary key |

| Data modeling | Relational database |

| Data type | |

| Database | Row |

| SELECT | |

| DISTINCT | SQL |

| Entity | Subquery |

| Entity integrity rule | SUM |

| Identifier | Table |

| IN | WHERE |

Exercises

Do the following queries using SQL:

List a share’s name and its code.

List full details for all shares with a price less than $1.

List the names and prices of all shares with a price of at least $10.

Create a report showing firm name, share price, share holding, and total value of shares held. (Value of shares held is price times quantity.)

List the names of all shares with a yield exceeding 5 percent.

Report the total dividend payment of Patagonian Tea. (The total dividend payment is dividend times quantity.)

Find all shares where the price is less than 20 times the dividend.

Find the share(s) with the minimum yield.

Find the total value of all shares with a PE ratio > 10.

Find the share(s) with the maximum total dividend payment.

Find the value of the holdings in Abyssinian Ruby and Sri Lankan Gold.

Find the yield of all firms except Bolivian Sheep and Canadian Sugar.

Find the total value of the portfolio.

List firm name and value in descending order of value.

List shares with a firm name containing “Gold.”

Find shares with a code starting with “B.”

Run the following queries and explain the differences in output. Write each query as a manager might state it.

SELECT shrfirm FROM share WHERE shrfirm NOT REGEXP ‘s’;

SELECT shrfirm FROM share WHERE shrfirm NOT REGEXP ‘S’;

SELECT shrfirm FROM share WHERE shrfirm NOT REGEXP ‘s|S’;

SELECT shrfirm FROM share WHERE shrfirm NOT REGEXP ‘^S’;

SELECT shrfirm FROM share WHERE shrfirm NOT REGEXP ‘s$’;